New Office, Reflecting Accessibility, Sustainability, and Thoughtful Practice

Private International Law (PIL):

a conflicts-law coordination layer

Introduction

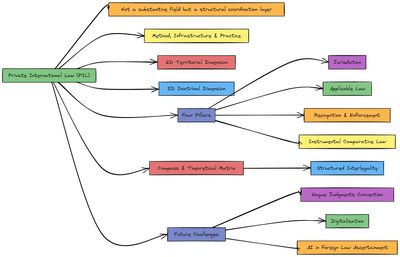

Within the Penteract model developed at Peeters Law, private international law (PIL) does not appear as a substantive field but as a conflicts-law coordination layer. It operates across the territorial dimension (2D) and is grounded in the doctrinal dimension (5D). This position reflects the methodological conviction that PIL is less an autonomous discipline than an ordering device of interlegality, structurally linking diverging legal systems.^1

Three classical pillars structure the discipline: (i) jurisdiction, (ii) applicable law, and (iii) recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. A fourth, less doctrinal but operational component — instrumental comparative law — concerns the practice of interpreting and applying foreign law in close collaboration with foreign counsel. This fourfold structure turns PIL into a structural crossroads of the multilayered legal order.^2

The Penteract Model in Private International Law

The placement of PIL within the penteract model requires clarification. At its core, the model views legal order not as a flat hierarchy but as a multidimensional construct. PIL emerges not as a substantive discipline but as a coordination layer that stabilises interaction between otherwise autonomous legal systems.^3

- The 2D Territorial Dimension captures the spatial allocation of state authority: jurisdiction, sovereignty, and the territorial reach of rules. This is the classic conflicts-law perspective, determining which court or country is competent to regulate a given cross-border dispute.^4

- The 5D Doctrinal Dimension reflects the plurality of substantive fields — contract, tort, family, succession, corporate law, etc. Each of these areas has its own internal logic, but when a dispute transcends borders, PIL supplies the structural “glue” that allows these divergent fields to interact without collapsing into incoherence.^5

The four pillars of PIL are situated at the intersection of these two dimensions. Jurisdiction lies primarily in the territorial layer; applicable law mediates between doctrinal logics; recognition ensures continuity across borders; and instrumental comparative law represents the practical mechanism by which domestic and foreign doctrines are made interoperable.^6

In this sense, the penteract model frames PIL as the invisible infrastructure of interlegality: a structural compass orienting legal actors when the territorial and doctrinal dimensions collide.^7

I. Jurisdiction

The determination of jurisdiction within the European Union is largely harmonised by the Brussels I bis Regulation.^8 Its general rule of actor sequitur forum rei (Article 4) is refined by special jurisdictional bases for contracts (Article 7(1)) and torts (Article 7(2)).^9 The Court of Justice has interpreted these provisions strictly to enhance legal certainty and predictability.^10

Tensions arise particularly in relation to exclusive choice-of-court agreements under Article 25. In Owusu, the Court ruled that the doctrine of forum non conveniens cannot be applied where the Regulation is applicable,^11 affirming the mandatory character of the instrument while restricting judicial flexibility. Critics argue this fosters predictability but undermines equitable case management, especially where the dispute is only loosely connected to the EU.^12

The CJEU has also clarified specific jurisdictional issues in Kolassa,^13 Car Trim,^14 Brogsitter,^15 Universal Music,^16 Holterman Ferho,^17 and Cartel Damage Claims,^18 highlighting tensions between economic efficiency and legal certainty.

Comparatively, the U.S. approach under the Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws^19 and the draft Restatement (Third) (2023)^20 allows more flexibility by relying on the “most significant relationship” test, showing that the EU’s rigid commitment to certainty is not the only model available.^21

II. Applicable Law

The determination of the applicable substantive law is governed by the Rome Regulations. Rome I sets out rules for contractual obligations,^22 privileging party autonomy (Article 3), while Rome II governs non-contractual liability according to the lex loci damni.^23

In the absence of choice, courts must rely on objective connecting factors (Article 4 Rome I). Scholars have debated the tension between predictability and flexibility, with Symeonides advocating for a functional methodology.^24 Recent comparative studies, including those from Hungary and Romania, show how localisation of damage remains contested in both theory and practice.^25

Rome II has raised questions regarding environmental liability and cross-border competition law (as in CDC Hydrogen Peroxide).^26 Specialised regimes further illustrate the diversity: the Succession Regulation,^27 the Hague Protocol on Maintenance Obligations (2007),^28 and ongoing debates on corporate mobility and the lex societatis.^29

CJEU jurisprudence such as Lazar,^30 Nikiforidis,^31 and Da Silva Martins^32 illustrates how Rome II continues to raise interpretative challenges. Comparative insights from Japan^33 and Latin America (Bustamante Code)^34 reveal alternative approaches to choice of law.

III. Recognition and Enforcement

The cross-border effect of judicial decisions forms the third pillar. Within the EU, foreign judgments benefit from automatic recognition subject to limited grounds for refusal (Article 45 Brussels I bis).^35

The Court in Gazprom underscored that mutual trust is the cornerstone of this mechanism.^36 Yet critics highlight that mutual trust sometimes collides with fundamental rights, particularly in family law and human rights-sensitive disputes.^37 The ECHR’s jurisprudence in Marckx,^38 Pla & Puncernau,^39 and Bosak^40 illustrates the corrective function of human rights review.

Cases such as Coman,^41 Hadadi,^42 Bohez v Wiertz,^43 and Child and Family Agency v JD^44 reveal how recognition in family law touches upon EU citizenship and fundamental rights.

Globally, the Hague Conventions remain central, notably the 1980 Child Abduction Convention,^45 the 1970 Evidence Convention,^46 and the 2019 Judgments Convention,^47 with UNCITRAL’s work on mediated settlements^48 and UNIDROIT Principles^49 adding further harmonisation layers.

IV. Instrumental Comparative Law

Private international law is more than a collection of abstract conflict rules. It also functions as a practical bridge across jurisdictions, compelling lawyers, judges, and scholars to engage with foreign law in concrete proceedings.

Belgium provides a telling illustration. Under the Code of Private International Law (WIPR), courts may be required to apply foreign law ex officio.^50 Yet in practice, this obligation often collides with practical constraints: judges rarely have linguistic or comparative expertise in the applicable foreign law. Consequently, they must rely on the parties or consult foreign counsel, turning litigation into a transnational collaborative effort.^51

Other systems adopt a different approach. Common law jurisdictions generally require the parties to plead and prove foreign law as a matter of fact,^52 while civil law jurisdictions tend to treat foreign law as law, obliging the court to establish its content independently.^53

The growing digitisation of law offers new prospects. Judicial networks, online legal databases, and emerging AI-driven comparative tools may reduce the evidentiary burden of establishing foreign law.^54 Still, the operational gap between theory and practice remains stark: the doctrinal duty to apply foreign law sits uneasily with the pragmatic reality of limited access and expertise.^55

This tension illustrates why instrumental comparative law deserves recognition as a fourth pillar of PIL. It is not merely a procedural adjunct but a constitutive element, ensuring that conflict rules do not remain hollow formalities but become workable solutions in transnational disputes.^56

V. Areas of Application

PIL plays a crucial role in:

- cross-border commercial contracts (jurisdiction clauses, Rome I),^57

- international family relations (Hague Child Abduction, Brussels II ter),^58

- cross-border succession (Succession Regulation),^59

- non-contractual liability (Rome II),^60

- corporate structures and real estate transactions with foreign elements (lex societatis, lex rei sitae).^61

VI. The Belgian Framework

In Belgium, the Code of Private International Law (WIPR) of 2004 provides a domestic framework.^62 It contains provisions on jurisdiction (Articles 5–14), conflict rules (Articles 15 et seq.), and recognition (Articles 22 et seq.).^63

Although subsidiary to EU law, the WIPR remains essential in situations falling outside the scope of Union instruments.^64

VII. Doctrinal and Judicial Sources

Leading doctrine stresses the methodological significance of PIL. Lagasse highlights its ordering function,^65 while Ancel & Kohen emphasise the growing role of soft law.^66 Verhellen provides a systematic account of international family law,^67 while Meeusen has published on the interaction between family law and European private international law.^68

Recent scholarship has sharpened these debates: Pataut has argued that mutual trust cannot override fundamental rights within EU PIL,^69 Mills has mapped the integration of international human rights into conflict rules,^70 and Trunk & Rogozina have explored PIL in the context of non-recognised states.^71 Kramer and van Hoek have analysed the procedural implications of globalisation on litigation,^72 while Dickinson has examined the third-country dimension of EU PIL post-Brexit.^73

Further, Fleischer has analysed company law conflicts,^74 Nishitani has illustrated Japan’s approach to foreign law, and Von Hein has done the same for Germany.^75 Together, these show the pluralistic fabric of PIL beyond Europe.

The European Court of Human Rights has equally shaped PIL. In Marckx, Belgium was condemned for discriminating against children born out of wedlock,^76 while in Pla & Puncernau the Andorran courts were reprimanded for violating the Convention in an inheritance dispute.^77 In Bosak, the Court stressed that refusals of recognition must comply with fundamental rights.^78

Conclusion

Private international law, in the Penteract model, is not a substantive field but a structural layer of coordination. It is at once method, infrastructure, and practice. Its placement in the 2D territorial and 5D doctrinal dimensions reflects its dual character: both a practical compass and a theoretical matrix. By embedding jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition, and comparative law into a coherent framework, PIL ensures that cross-border adjudication is not a matter of chance, but a structured process of interlegality.

Future challenges — from the Hague Judgments Convention to digitalisation and the role of AI in foreign law ascertainment — show why this model is not merely descriptive but normative: it points to how PIL can continue to serve as the connective tissue of a pluralist, globalised legal order.

For full bibliographical references to the cited works, please contact Peeters Law.

Peeters Law

Jos Smolderenstraat 65, 2000 Antwerpen, Antwerp, Belgium